In 1982, on the foothills of the road to Nigeria’s 1983 general elections, it was quite clear that the ruling National Party of Nigeria (NPN) had no plans to declare a vacancy in any significant political office around the country. Instead, they seemed bent on consolidating power in order to avoid a remake of the judicial nail-biter that yielded the presidency to Shehu Shagari in 1979.

The essential party positions featured a stellar cast. Adisa Akinloye, the party chairman, was a veteran lawyer with political experience predating Nigeria’s independence. The energetic Suleiman Takuma ran the party secretariat and Trade Minister, Umaru Dikko, was the ruthless campaign strategist. The job of guaranteeing the outcome that the party sought to engineer, however, fell on Sunday Adewusi, the then Inspector-General of Police (IGP). The son of parents from Ogbomoso, Adewusi grew up around Keffi in what later became Nasarawa State. He graduated at the top of his cadet set in 1958 and, at 45 in 1981, he was appointed Nigeria’s youngest ever IGP.

As Inspector-General, Adewusi headed the armed and uniformed wing of the NPN. For the elections, his genius lay in his ability to depute just the right kind of officers to the places where the party needed to manufacture results. Then, as now, the ruling party felt called upon to claim the politically prodigal south-east of Nigeria as part of its realm, irrespective of the will of its people. For this purpose in 1983, the NPN desired to capture old Anambra State which happened also to be the home state of Nnamdi Azikiwe, Nigeria’s first post-colonial Head of State and at the time leader of the NPN’s estranged political partners, the Nigerian Peoples’ Party (NPP).

For the job of softening up Anambra State, Adewusi found just the right man in Bishop Eyitene. The “Bishop” in Eyitene’s name was not an ecclesiastical office nor was it a Pentecostal title. Bishop’s tenure as the Commissioner of Police in Anambra State was an extended bout of political Jiu Jitsu with then state governor, Jim Nwobodo. Their politically irreconcilable co-habitation became the subject of bitter litigation, all designed, it seemed, to open the political flanks of the governor and his party. It worked a treat.

On behalf of Adewusi, Eyitene won litigation before the Court of Appeal asserting the autonomy of the police on questions of personnel postings. For accomplishing his political task with aplomb, Adewusi rewarded Bishop with redeployment to Lagos ahead of the 1983 election. The new team he sent to Anambra State routed Jim Nwobodo and his NPP in the governorship election. It was left to the Supreme Court to certify the beauty of Adewusi’s handiwork and they duly obliged in December 1983 before the military sacked the lot of them.

37 years later, the Supreme Court relied on numbers confectioned by a rogue Commissioner of Police to declare in January 2020 that the man who came fourth in the governorship election in Imo State the previous year was in fact the winner. Today, the judge who rendered that judgment leads Nigeria’s judiciary.

This past week has offered up a rich advertisement of the convenient partnership between judges, the police, and politicians.

In Rivers State, the Inspector-General of Police clearly took sides in the political contest between incumbent governor and his immediate predecessor, who is now the Minister of the Federal Capital Territory and who also desires to be known as the godfather-general of Rivers State. First, he sought to arrest scheduled Local Government elections in the state on the artifice of obeying a court order. The problem is that there were two court orders not one, from what lawyers would call courts of co-ordinate jurisdiction. The High Court of Rivers State in Port Harcourt had mandated that elections occur on 5 October. In requiring the police to withdraw from providing security cover for the vote, the Federal High Court in Abuja effectively ordered that they should not.

Thwarted by what appeared to be a spontaneous civic revolt, election day witnessed uniformed police officers under the command of the IGP going from station to polling unit to cart away ballot boxes and tear down the displayed rolls of voters. The day after voting, supposed winners having been sworn in, the IGP announced the withdrawal of his officers and men from the state. As if on cue, practiced arsonists descended on Local Government secretariats, burning and destroying them one after the other.

In neighbouring Edo State, meanwhile, the IGP’s situational commitment to obeying court orders failed him. Lawyers for the governorship candidate of the Peoples’ Democratic Party, (PDP), Asue Ighodalo, armed with the duly served order of a competent court to inspect election materials found their way into the state headquarters of INEC in Benin first blocked by a wall of uniformed police officers. When the police requested for reinforcement, they were joined not by units of more police assets but by thugs of the ruling party.

The Nigeria Police Force is the oldest institution in the country and also the largest single employer of labour. Its personnel just happen also to be both uniformed and armed. Under the Constitution, the president appoints the man who heads the Police and that appointee is also obliged to take operational orders from the president. Historically, therefore, the position of the IGP has always been fraught and successive incumbents have mostly been prepared – with a few exceptions – to manage this delicate relationship with skill and professionalism acquired through exposure to their predecessors and to high-level leadership training.

Much of this training was missed by the current incumbent, Kayode Egbetokun, while he spent much of his time in the Force as long-term Aide-de-camp (ADC) to the current president. His claim to the job therefore lies in personal fealty to his benefactor. For this, he has been handsomely rewarded, first with expedited preferment to a role for which his preparation falls short and, second, with a targeted amendment of the law to extend his tenure in order that he will be around to pre-determine the 2027 elections.

In November 2009, Kayode Fayemi, then an opposition candidate, took temporary leave from the protracted legal tussle over the outcome of the governorship election in Ekiti State in South-West Nigeria two years earlier in which he was involved to travel to New Orleans in Louisiana, in the United States of America, to address the annual conference of the African Studies Association on “Electoral Politics and the Future of Electoral Reform in Nigeria.”

In a deeply thoughtful delivery, Fayemi feared that “the quest for consolidating our democracy is now in retreat and risks encountering outright reversals.” He explained that there are “five ‘minigods’ that one must pay significant attention to in any attempt to understand the nature of electoral politics in Nigeria”. These include the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), “which often acts like a Siamese twin of the ruling party….”; the security agencies – particularly Nigerian Police Force; “thugs and bandits”; the judiciary; the money god.

20 years ago, the late Innocent Chukwuma and I met with Tafa Balogun inside the office now occupied by Egbetokun to discuss a document he had commissioned from us. After reviewing our recommendations, Tafa looked at us with the full majesty of his corpulent authority and told us that he was inclined not to proceed with our suggestions. Almost wistfully, he added that when it was someone else’s turn, the person could do what they wanted. It is now Egbetokun’s turn and, as Inspector-General, he has turned Fayemi’s predictions of electoral dystopia supervised by the troika of the police, bandits, and crooked judges into a manual of policing. It just remains for police officers to be required to sing: “On your mandate we shall stand….!”

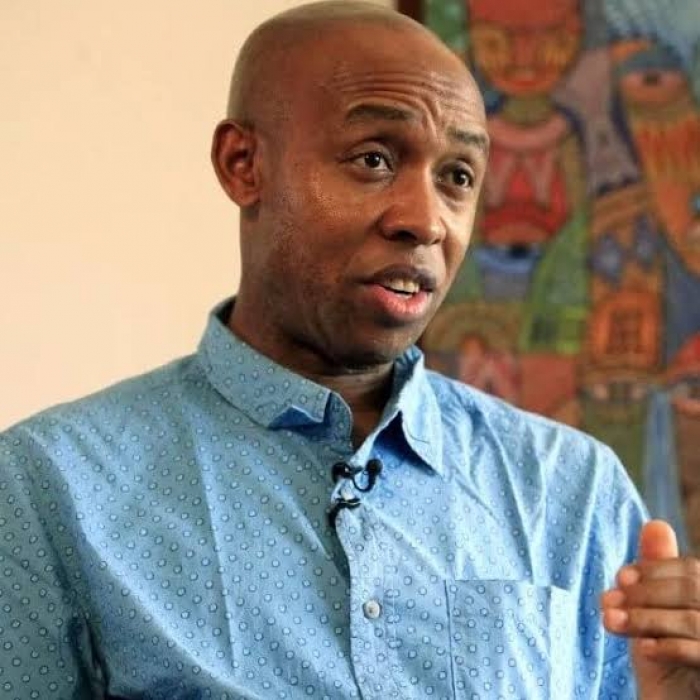

** Chidi Anselm Odinkalu, a professor of law, teaches at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and can be reached through This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..